Fabulous article on the democratisation of luxury in Fortune magazine. I just had to reproduce the entire article here.

****

The next time you're waiting for your bags to arrive at O'Hare, ponder this: In Milan there's a leather goods store called Valextra, just down the road from the famed La Scala opera house, whose signature product is a line of exquisite luggage quite unsuited to modern life.

The suitcases, which start at about $5,000 apiece, have no wheels, no pull straps, no retractable handles. Most striking of all, they come in gorgeous white leather with a subtle creamy hue that would scuff instantly if checked onto a commercial airline. As Valextra sales assistant Martina Terazzi discreetly points out, they are best suited for people who travel by private jet.

This is what "luxury" used to mean: beautifully crafted, hideously expensive, and unashamedly elitist. Owning such items was not just a question of wealth; it was also a question of class. Luxury goods were sold in stuffy stores with intimidating personnel in white gloves who glanced at your shoes before deigning to show you their merchandise.

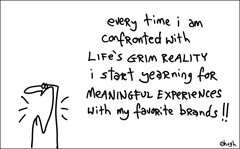

Today that's the exception. For the most part, luxury is no longer reserved for the spoiled rich. Increasingly it is the domain of the global middle class on an ego trip - people from Indiana to India prepared to pay a premium for the thrill of owning something that makes them feel special.

Luxury houses like Dior, Cartier, and Chanel have made fortunes by extending their product lines to cater to such aspirations. And we're not just talking about the traditional accessories. Armani sells chocolates. Prada has a cellphone. "We are not in the business of selling handbags. We are in the business of selling dreams," says Robert Polet, chief executive of the Gucci Group. (And at Gucci those dreams can come true for as little as $80 - the price of a box of playing cards.)

Although stock prices have taken a hit in recent weeks, luxury sales have boomed along with the global economy. The world market has doubled in the past decade to about $220 billion a year in retail value. That has encouraged many companies with less pedigree to try to muscle their way in. They call themselves purveyors of "accessible luxury" and claim to be both classy and good value.

Coach is a prime example. Starting in the mid-1990s, CEO Lew Frankfort repositioned the stodgy leather-goods firm as a less expensive Louis Vuitton and watched its $300 bags fly off the shelves. Mass marketers are getting in on the act too. H&M first teamed up with Karl Lagerfeld in 2004 and now works regularly with big-name designers. Target deals with Mossimo Giannulli and Isaac Mizrahi. Through these partnerships, says Target VP Trish Adams, "our guests have learned - and come to expect - that high fashion doesn't have to mean high prices."

This jostling for position raises a fundamental question: What does luxury mean if everybody claims to be doing it? "It has become one of the most overused words in the English language," sniffs Simon Cooper, president of Ritz-Carlton, the hotel chain once synonymous with a gilded existence and now slugging it out with a host of competitors. "You can't find an ad even for the cheapest car that doesn't have the word 'luxury' in it."

The question applies equally to the high and the low end. It's easy to understand that a $220,000 Louis Vuitton Tambour Tourbillon gold watch is a luxury item, but can the same be said of $275 Vuitton sunglasses? Is a Stella McCartney collection designed for H&M any different in status from Stella McCartney's collections for her own brand, which is part of the Gucci Group?

Wall Street's answer: Relax. Luxury has become one giant pyramid, it reckons, with brands like Cartier and Vuitton at the top and Coach near the bottom. From its perspective, anywhere in this pyramid is a great place to be, since luxury firms trade at a premium, and industry analysts predict that the market will keep growing at an annual clip of 8% to 10%.

Yet within the sector itself, there's furious resistance to the notion of lumping everyone together. Louis Vuitton chief executive Yves Carcelle is scornful of the idea that most of the others in the pyramid are even competitors. "The confusion does not exist," he says. "Consumers are much more intelligent than one imagines. There are just a limited number of houses that respect the rules of luxury." By that he means predominantly old-line European firms with time-honored traditions, the highest standards of craftsmanship, innovative design, and a selective distribution policy that usually includes a network of wholly owned stores and strict controls on licensing, discounting, and anything else that could hurt a brand's reputation.

Peter Marino, who designs those costly Vuitton stores, argues that the whole point of luxury is that it isn't accessible to everyone. "Coach has nothing to do with luxury," he says. "It could be selling iron ore, but it just happens to sell handbags. This is not about girls in China with a sewing machine, but about workmanship, exclusivity, and the sheer gloriousness of the materials." At Gucci, Polet plays down Stella McCartney's 2005 collection for H&M. "It was just a one-off that reinforced the global scale and importance of the brand," he says.

The accessible-luxury crowd is equally adamant. Mizrahi decries critics of his work with Target as "brand racists" and says "it's nearly impossible to be luxurious without mixing it up and keeping it real." At Coach, CEO Frankfort concurs. "When did they last speak to a consumer?" he asks of his detractors. "Luxury has been democratized." As for quality, Frankfort insists that Coach bags "are as well made as products anywhere. We even source from some of the same tanneries as European houses. But because we manufacture in low-cost countries, we can pass the savings on to consumers."

Mass vs. Class

So who's right? Neither side is on particularly solid ground, because even the stuffiest companies are stretching themselves wide to appeal to a range of consumers. What's unquestionable, though, is that the key to luxury today lies in creating an emotional rapport between the consumer and the product. If enough consumers believe it's luxury and are prepared to shell out accordingly, then luxury it is.

The hard part is what Stefania Saviolo at Milan's Bocconi University calls the "art of dream maintenance." It means thrilling your customers and bringing them back again and again. For the accessible-luxury players, the challenge is keeping up quality and design as they produce wave after wave of new products. The big-name houses have an easier time because of their tradition of craftsmanship and strong legacies.

Visit the Milan office of Ermenegildo Zegna, CEO of the eponymous men's wear firm, and you'll find a picture of his grandfather's woolen mill in Trivero, where the firm began in 1910 and where much of its production is still based. "More and more customers want to know what is behind the brand," Zegna says. The firm sells a lot of $2,500 suits, of course, but in the past four years it has also rolled out its own fragrance and sunglasses. This fall it will introduce a line of underwear.

Stretching your brand like this can be risky, even for the most history-laden houses. "Diversification is the rule of the game, but you can't do everything," warns Francesco Trapani, CEO of Italian high-end jeweler Bulgari, which has gotten into hotels and is about to launch a line of skin-care products. "The danger is, you do something badly, and then you don't just lose money but your reputation."

There's also a risk of overexposure, particularly in Japan, which accounted for as much as 40% of worldwide luxury demand over the past decade. Already, 94.3% of Japanese women in their 20s own a Louis Vuitton item, according to one Japanese research institute.

The nightmare scenario is that your brand suddenly becomes banal or vulgar. That happened to Pierre Cardin, who pioneered the use of licenses in the 1960s only to lose control of the hundreds of products that ended up bearing his name. For a while it happened to Burberry. A British outerwear company best known for its trench coats, it underwent a transformation in the 1990s at the hands of an American CEO, Rose-Marie Bravo, who used Burberry's distinctive plaid on products from bikinis to strollers.

That made it a hit worldwide, but her strategy backfired in Britain when soccer hooligans and tart-tongued tabloid actresses adopted the Burberry plaid as their own status symbol. For a time, nightclub bouncers in Britain refused entry to people wearing Burberry caps. The firm succeeded in containing the problem to Britain and moved aggressively to resolve it. Christopher Bailey, brought in as designer in 2001, has deemphasized plaid and played up other icons of the brand, such as a horse and knight. He describes the new look as "disheveled elegance - it's luxury, but there's a familiarity about it."

Drinks companies faced a similar dilemma when rap stars feted Cristal champagne and Courvoisier cognac in their lyrics. That helped boost sales, but it made some executives uncomfortable. Last year rapper Jay-Z called a boycott of Cristal after interpreting remarks by one of the maker's executives as racist.

But at least some wealthy people aren't interested in the familiar. As the number of high-net-worth individuals in the world has doubled in the past decade, Vuitton, Cartier, and others are in a race to the top to woo them. Even as they look to extend their brands downward, they are offering limited-edition or one-of-a- kind products at stratospheric prices.

Buy that $220,000 Vuitton Tourbillon watch and the company will incorporate your zodiac sign on it. Or perhaps you'd prefer the ultra-limited edition: one of just five trunks containing 33 Marilyn bags, each in a different shade of crocodile leather, for which Vuitton won't disclose a price. CEO Carcelle says that these "über-luxury" items account for a minority of sales, but that it's a high-growth area. "There is demand for things that are incredible and unique," he says.

And we're not just talking about Russian billionaires. Burt Tansky, CEO of Neiman Marcus, told a luxury conference in June that the expensive-accessories business at his stores, including shoes with $600-plus price tags, has "just gone crazy." Luxottica, the Italian eyewear company Luxotica that makes sunglasses for Versace and Bulgari, reckons there's enough demand for shades costing $1,000 or more that it's rolling out a new line of high-end retail stores starting in New York City this fall.

Is the sky the limit? Hennessy is testing to find out. The spirits company is selling a limited edition of 100 bottles of cognac for $200,000 a bottle. It's a blend of the best eaux de vie in the house, but a big part of the attraction - and price - comes from the packaging: a case surmounted by Venetian-glass pearls and fashioned by artisans who usually make stained glass for cathedral windows. "It's more like a work of art than a consumer product," says Moët Hennessy president Christophe Navarre.

Even so, $200,000? At rival Rémy Cointreau, Christian Liabastre is too polite to criticize the competition directly. Rémy has its own limited edition called Black Pearl that it released last year in a Baccarat crystal flask. It retails for about $10,000. No, he's not tempted to follow Hennessy's lead. "You can't say this is perfection," Liabastre says, pointing to the Black Pearl flask, "and then come back later and say, 'We've got something even better."

Tell that to hoteliers in an age when seven stars is the new five. At the Plaza Athénée in Paris, owned by the Sultan of Brunei, where a standard room costs $950 a night, chief operating officer François Delahaye strides through the flower-bedecked lobby, pointing out the historical fixtures and the formal Michelin three-star restaurant.

Then he rounds the corner to show off his pride and joy: the bar, revamped to look like an ice cube, complete with video image of a crackling fireplace and a carpet woven from a pixelated close-up of Madonna's face. "Big shock, right?" he asks. It's all an attempt to bring in a younger affluent crowd. "The sons and daughters of our guests," he says, "are fed up living with Louis XV style." The contrast is jarring, but in some ways it symbolizes the restless state of luxury today. It's a world in which the snobs want to be a little bit populist, the populists want to be a little bit snobbish, and everyone has his fingers crossed that the extraordinary demand of the past decade will continue unabated.

Source and images: Fortune

No comments:

Post a Comment